(Click here to scroll to the main summary)

Context:

I recommend that my TAs keep a three-column gradebook, a recommendation built from my own instructional and TA practices. Several of my former TAs report that they have adopted this system for their other courses and work, including as instructors. The recommendation in short, as summarized below, is to provide three separate grade values for each key grading item.

I write this in particular for TAs and Instructors adjacent to Philosophy, or in disciplines which commonly grade holistically/heuristically. But the same practices can be useful even for disciplines and courses using very strict arithmetical rubrics that have been validated across courses.

I also mention Excel a few times, since that is what we license at UofT and what I train my TAs on. But most of the following can be done in other spreadsheet software or even manually. Just make sure that whatever practice you choose abides by the appropriate laws and policies around protecting student information. At UofT, this TATP page summarizes privacy and confidentiality in teaching (click to open in a new tab). What they call “portal” on that page is what you currently know as “Canvas” or “Quercus”—it was written before our latest learning management system migration.

On a later resource page, I’ll provide more guidance about how to set up a gradebook to support or streamline grading. Here, I just introduce what I’ve descriptively called the three-column approach. (I’m sure there’s a better name for this somewhere in the literature; if you know it, let me know!).

The approach, in brief:

The three-column approach just means that you dedicate three columns for every key grading item, filling them in as you grade. This means you’ll generate three values for every key item. These three columns are:

- The lowest score you think a student submission could fairly receive, on your strictest fair interpretation of grading guidelines (in the context of the course, assignment, and rubric etc);

- The highest score you think that student submission could fairly receive, on your most lenient fair grading approach (in the context of the course, assignment, and rubric etc);

- The proposed score you would initially assign for that submission, which will fall somewhere in between the previous two values.

In short, you are providing an initial proposed score, as usual, but also setting up a confidence interval for those scores. These are input into the gradebook as you are grading, along with any other columns or grading notes. That’s it! That’s the whole suggestion!

Why do this? In brief, I think it helps give important data to guide and support benchmarking and standardization of grades, and identifying possible errors or biases, while also helping support TA confidence and time management. I elaborate on these briefly below. Finally, it also helps me when reviewing a request for regrading or just a request to discuss a grade, especially in a large class where I cannot spontaneously recall my earlier grading impressions. While I also keep a separate column of personal notes for this reason, having the three separate grade values as part of my grading notes helps me to recall and situate my feedback, and to frame the students’ requests against my fuller initial impressions.

Some motivations:

In initial benchmarking:

Typically, TAs and the instructor will meet at the beginning of a grading period to “benchmark” assignments. A main goal of this meeting is to get on the same page about grading expectations, typically by reviewing a representative selection of submissions and discussing the grade they should receive.

Of course, we might not always pick a truly representative sample, and it might be that three benchmarked papers are insufficient guidance for another hundred papers, etc. I have often found both to be the case, both as a TA and as an instructor. In rare cases, benchmarking sessions led to even less clarity on how a rubric was to be applied, or how unexpected cases should be graded.

This is why initial benchmarking is not the only benchmarking you’ll do—you’ll often do iterative benchmarking/standardization as you grade, checking your earlier grading scores against later ones, for example, or comparing with other TAs. Still, we need to start grading somewhere; initial benchmarkings are one such starting point.

In those initial meetings, I recommend you ask for all three data points: not just what grade the submission should receive, but what the highest and lowest it could receive are. As a TA (and as an instructor!), I often found that my disagreements with others’ grading intuitions more often came down to the proposed grade than a grading interval. That is, we might agree that a paper is between a B- and a B+ at the extremes, but disagree whether it is more specifically a 73 versus a 77. This disagreement is important to note and discuss, but is a bit easier to discuss knowing we have the same grading boundaries.

Importantly, since benchmarking is about setting out broader grading guidelines and practices, knowing these boundaries gives you more information about grading thresholds, more data against which to compare subsequent submissions, and information about where grades might sit within a given confidence interval. It might be that the question of 73 versus 77 is best left unsettled until we’ve reviewed a more representative sample, while setting out the necessary or sufficient conditions for a B- or B+ can nonetheless provide important guidance.

Errors and biases:

There are many possible sources of error and bias in grading. I believe the three-column approach can be helpful as one resource for addressing these issues, if only because we have more data for comparison. Consider two use cases:

First, if I make a transcription error in one grade value, I can more easily identify this if I have two triangulating grades. If my grade range is 65-75, and I propose a grade of 76, then I have probably mistyped either the 75 (perhaps meant to be 78, but with a slip on the number pad) or the 76 (perhaps a transcription error for 67). Or perhaps I had simply reassessed it, but failed to upgrade the confidence interval. If I only record a 76, this error is much more difficult to identify without further redundant recordkeeping.

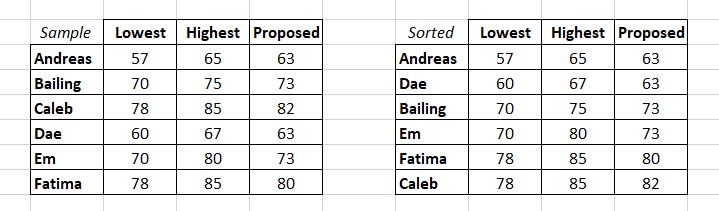

Second, I can sort my gradebook by the confidence interval, and/or by the proposed grade, to see if there are obvious discrepancies between two otherwise similar items. See the below screenshot of a simplified fake gradebook.

In this example, I sort the original data set [left] through three filters [right]: first by the lowest score, then the highest, then the proposed. This will sort the confidence intervals from low-and-narrow to high-and-broad. In the example, there are a few things that might draw my attention.

First, Fatima and Caleb have the same confidence interval (78 to 85), but Caleb is scoring a few points higher than Fatima in the proposed column (82 versus 80 respectively). That difference may be perfectly warranted: it’s possible to receive the same score for different reasons, and the same applies to confidence intervals. But it might also identify an error or bias in my grading, if not merely a case where I can or should standardize.

Second, Andreas and Dae have the same proposed score (63), despite having different but overlapping confidence intervals (57 to 65 and 60 to 67 respectively). I might wonder if Dae’s submission, having a higher general confidence interval might warrant a higher overall score. It might, it might not. Perhaps I just graded one of them at the beginning of my grading and one at the end, and this demonstrates change in my standards (a reason why, though not addressed here, it can be useful to indicate in the same spreadsheet when you graded a given work). Regardless of whether the scores are warranted, this may be a case I wish to review.

Third, Bailing and Em also have the same proposed score (73), and while I have assigned the same lower threshold to both (70), the highest possible grade for Bailing is much lower than for Em (75 versus 80 respectively). Again, this might be perfectly warranted, but it might also warrant a quick review for error, bias, or standardization.

In all these cases, having only the proposed grade will not be as helpful in identifying any possible issues. Meanwhile, I can use these data points when addressing other possible biases. Maybe I’m looking to see if there are alphabet biases (especially if I’m grading in name order), temporal biases (based on which submissions I graded first/last, or on which days and in which moods), biases within a specific question or topic (grading one topic more leniently without strong justification), or implicit biases related to the identity of the student. Again, these can be easier to identify with more data points. If I wrote grading notes to myself, this might be even easier to navigate.

Standardization:

The above two sections largely spell this out already. Depending on how an assignment is designed and developed, there can be a few ways to “standardize” grades. In the loosest sense of this term, I just mean that we are making sure we have graded everyone on an equal standard. This could be identified by sorting the gradebook in the ways described above, to ensure that any outliers are appropriately addressed.

In a case where there is less confidence about the proposed final grades, such as whether there is a defensibly meaningful difference between a 73 and a 74, we can also develop a standardization protocol based on the confidence intervals. This could be [perhaps unfortunately] appropriate in courses with high grading loads, where it is nigh impossible to give a secondary review to dozens of submissions or more. This might also be appropriate in cases where submissions cannot be easily measured against a rubric in a reliable way

While I do not adopt this in my own courses, you could quite reasonably decide that the final grade is the rounded median of any given confidence interval, or the high value, or the low value, or some similarly calculated value. This would ensuring that students with identical high/low scores receive the same final proposed score. In the example above, this may look like giving Fatima and Caleb identical scores, but Em a higher score than Bailing. Whatever approach is determined to be fair and appropriate in your grading context, again, having more data points can help with standardization.

Time management:

For me, this practice also helps with time management, though your mileage may vary. This may seem counterintuitive: wouldn’t determining and inputting more values take more time?

When I used to grade with just one value, I was often still doing the same amount of work, if not more. I would mentally hone in on a proposed grade, negotiating the appropriate range and the grade’s place in that range. This was especially true for the first submissions I would grade in a batch, since I would be spending more time trying to “perfect” the grading standards that I would be following later, while still knowing I’d be returning later to check that those standards were consistent. At times, this had the whiff of unfair grading too: spending more time on a given set of submissions might bias me to more scrutinous grading, more thorough or selected feedback, or other differences against later submissions.

Using the three columns just externalizes a lot of this mental work, and allows me to automate some of it in Excel or other software. In the very least, it at most takes me the same amount of time, but more often it takes me far less time. I attribute about a third of my time savings in grading to adopting this technique.

As hinted above with benchmarking, unless you have a strict and well validated arithmetical rubric, there can be a lot of changes to benchmark settings throughout the grading process. I might happen to grade a non-representative sample of papers in the first few submissions, just because of randomization or chance, and might end up exaggerating the differences between those papers. I might notice trends across dozens of tests that seem mere outliers in a select few, etc.

Knowing and appreciating that I’ll be revisiting grades helps me to more easily record values and move to the next, while inputting multiple values helps to streamline and inform that standardization process at the end. On a more involved side of things, I can use Excel to quickly formulate grading distributions for each of the columns, identify and investigate any aberrant trends, and avoid needing to get it perfect the first time around.

Confidence:

When grading a new assignment, new topic, or new course, we can often feel less confident in our grading decisions. My TAs are often in this boat: being asked to grade content outside of their research areas, and even some assignment methods not common to the discipline. (How do you grade a dance in philosophy?). This feeling can persist even with ample support. At least, it persists in me and some of my TAs, and contributes to some of the time sink described above.

The three column approach helps me offload some of the mental gymnastics early in grading, and to minimize the feeling that I must get grades perfectly the first time through. Having the “confidence interval” is a plain way of recording my confidence, so to speak. Meanwhile, having more data points from benchmarking to standardization can help me develop more standardized and fair grading practices even when the rubrics provided to me are vague or heuristical. They can help me track trends, errors, and biases with more ease.

Even if the approach does not make me more confident, it gives me more tools to address the core concerns around that lack of confidence. Several of my TAs report the same.