In conversations with students, and in browsing through our school’s various Reddit communities, I often see questions, concerns, and even misconceptions about what grades are, what they mean, and what makes for a “good” grade. This page summarizes some chats I’ve had with students, pulled together from emails, class discussions, and office hours. My hope is it will give context to your grades and how grading works. Of course, the most direct answers about grading will often need to come from your own instructors or graders, since things can vary between courses and assignments. Nonetheless, you can use this as one further resource available to you.

This page has a lot packed into it, and I’ll likely add more depending on the other questions I receive. It’s designed to be read linearly, but you’re welcome to just jump around. To facilitate this, I’ve embedded some links to help jump around, and added a bit of repetition for those skipping through. As always, searching with CTRL+F or your browser’s equivalent is a helpful way to find what’s most useful to you.

On this page (click to automatically scroll down)

- “Will my grades drop from highschool to UofT?” Reframing letter grades

- “What is a good grade?” Understanding the FAS grading scale

- Assignment grades versus course grades: FAS Statement in context

- “What is a good GPA?” Understanding the cGPA

- “Where did I lose marks?”

- “Why is my feedback so brief?” Understanding grading context, and feedback as a scarce resource

- The relationships between grades and feedback

See also (opens in a new tab)

“Will my grades drop from highschool to UofT?” Reframing letter grades

If you’ve recently joined UofT (or another university), you likely heard the warning that your grade will “drop” between secondary school and university. That is, many students used to getting high As and Bs will suddenly be receiving Cs or even Ds. Some of this might be attributed to changes in learning styles, to acclimatizing to a new type of living away from home, etc. After all, university is a transition in any ways. But often it comes down not to changes in students, but changes in what those grades mean. Focusing on letters out of context can be misleading.

Consider it like this: Most students who get into university are used to receiving high scores in secondary school. After all, grades are one key determinant of who is admitted. (There are some problems with this approach, ranging from equity issues to grade inflation in secondary schools, but let’s set those aside for now). The consequence is that most students have been getting grades just in the 90s and 80s.

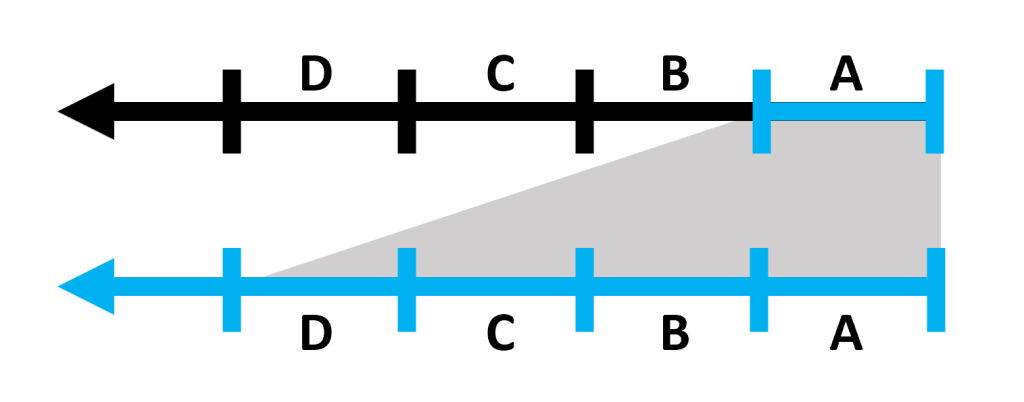

Because we’re doing more advanced work, and largely working within that smaller grade range, we want to be able to get a more nuanced distinction between some of these grades. We want to be able to distinguish more clearly between an 85 and a 90, and all the steps in between. So, we take the top of the grading scale and we zoom in on that range, stretch it out.

Here’s a very non-technical visual aid, just to help illustrate what I mean (not at all to scale, etc):

The letter “C” means something different in university than in highschool. Your score isn’t necessarily dropping when you jump to university (though it might – it’s still a transition!), rather it is being reframed in this more nuanced grading scale.

The same applies to numbers. At UofT, a 68% is a “C+” and many students in first year courses especially will get scores around a 68% (our median in large entry courses is usually around a 70%). But these are nearly all students who received 80% or higher in highschool. Has their work suddenly dropped in quality that severely? Not likely. Rather, that 68% means something a bit different than in highschool.

You’re going to be studying some new things, writing some new assignments, and generally trekking through new territory. Where grades are partially a way of measuring your mastery over the course learning outcomes, it’s quite reasonable that not everyone will demonstrate strong mastery on a new and advanced task. That doesn’t mean you’re suddenly doing worse than in highschool, it just means we’re now exploring something more advanced, and grading it on a different scale

So, will your grades drop? In the original sense of the question, it’s quite likely, yes. But it’s often better understood as a consequence of relabelling your performance against university expectations, rather than any necessary decline in your performance or drastic increase in our expectations.

The rest of this page looks a bit more at what these grades mean at UofT, and some context for grading.

Click here to scroll to top of page.

“What is a good grade?” Understanding the FAS grading scale

The courses I teach fall under the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) Statement on What Grades Mean (click here to open in a new tab). That statement “defines” what certain grades mean in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at UofT, and roughly applies to the other faculties as well. I encourage that you check it out. When I am designing a course, I make sure that the total learning and assignment outcomes map onto that statement. When I am designing an assignment rubric, I make sure that the rubric generally fits that statement too. (I say “generally” because of the reasons I explain below, about assignment grades versus course grades).

This statement is helpful, and it reminds us that doing C-level work is still making important progress and meeting university expectations, while B-level work is by definition “good”! Where students often obsess over their grades and standing compared to an idealist 100%, it can be reassuring to remember that a 73% is a good score by definition.

Still, you might find that page quite vague at times. I know that I do. What is “evidence of grasp of subject matter” and how is that different than “understanding of the subject matter” etc?

This vagueness is mostly deliberate: we need these definitions and grades to work across many different types of assignments and courses. Getting more specific might make the Statement less flexible in its application. Still, while it makes sense to define these broadly, it also means that students will rarely find it informative. I know I didn’t as an undergraduate!

Let me say a few things to help contextualize and unpack some of the Statement.

First, completeness

The language of completeness does not appear on the Statement, but is lurking behind most grading criteria. As I suggest on another page about writing papers as assignments (opens in a new tab), it is possible to write a strong paper that is not a strong assignment, just because that paper missed some key requirements. Grades are determined by how well a submission completes and masters the requirements for that assignment. So we can gloss this first as a matter of completeness.

For some finer-tuned guidance, I like to recommend that students look at the rubric from the University of Victoria’s academical and technical writing program (click here to open in a new tab). That rubric does not apply to all of UVic, and it does not apply at all to UofT. After all, we’re a completely different school. Still, I like it as a supplementary resource, because it breaks down broader grade ranges into more discrete steps, and gives a bit more indication of the criteria that might establish that grade step. It’s helpful to think about how the threshold for a “good” grade might minimally demand that I have met every assignment requirement — that my assignment is complete and meets all requirements completely. That’s something that is often considered common knowledge at UofT, but which is not transparently in the FAS Statement.

In general, if I am missing any core assignment requirements as a student, it’s going to be quite difficult to earn a higher B-range grade. If I was asked, for example, to consider an objection and reply to my argument, and I’m missing these, then it will be harder for me to earn a higher score because my assignment is incomplete. To get a “good” or “excellent” score on an assignment, I will need to have completed that assignment, as an assignment.

Second, active understanding

In the FAS Statement, scores are often expressed in terms of knowledge and understanding. In the D-range through B-range definitions, there is a focus on the grasp of subject matter, familiarity with literature, understanding of issues. However, when we look at the higher B-range and A-range scores, the focus is less on how much we understand, and instead, what we do with that understanding. Here we seem to have more active verbs like analyze, criticize, evaluate, and synthesize. These are verbs describing what we do with that understanding once we already have it in hand — once we’ve grasped it.

Consider an example. It is one thing to memorize and repeat that apoptosis commonly plays a role in differentiating digits in human foetal development. With some studying, you could just memorize that previous sentence and repeat it back to someone even without knowing that that sentence means: without knowing what digital differentiation is, or what apoptosis is and its mechanisms. So memorizing might be a sign of some active learning and understanding, but even more active understanding would require some further depth or application. Perhaps we could also ask whether we would expect the same thing to be true of apoptosis in other species, or whether syndactyly might be explained in terms of apoptosis, or whether differentiation might be explained better by other mechanisms, etc. These questions reflect the more active verbs in the A-range and B-range of the FAS Statement, since we’re not merely showing that we learned that apoptopsis plays this role, but are evaluating that role, critically reflecting on the possible evidence, generating hypotheses, etc. We have that initial understanding, and we’re actively doing something with it.

Similarly in philosophy papers: It’s one thing to repeat an argument or objection that was covered in class materials, or to use technical terms correctly; it’s another to be able to assess those for validity and soundness, or to generate objections; and it’s another still to develop your own arguments, defending them against candidate responses, and identifying how they extend beyond what was covered in class materials. These latter abilities track onto the higher end of the grading scale, demonstrating more mastery over the skills and materials in a course.

Third, evidence and clarity

One last thing to point out for now: the FAS Statement often uses the word “evidence,” such as in “some evidence of familiarity with subject matter” or “strong evidence of original thinking.” This is important, since instructors and graders cannot read minds and intentions: we can only grade the assignments that are submitted. We’re not grading people, we’re grading coursework.

For example, perhaps you understand the course material very well, but write “Thomas Nagel argues that we can know what it’s like for a bat to be a bat” instead of “cannot know.” That’s a relatively small typo of three letters, but it radically changes the sentence. If this is the only sentence in the whole paper about Nagel, then it would not be good evidence that the author understood Nagel, since it says roughly the opposite of what Nagel argues. If this is surrounded by other summary and argument that clearly does reflect what Nagel said, then this typo can be understood as an error in context. But without that competing evidence, we must rely on the evidence as presented; we cannot simply read minds for what might have been intended.

It’s my job not only to make sure that I’m following instructions, but that I’m making it clear and giving evidence that I have done so.

So, I take this use of “evidence” in the FAS Statement to point out a third important thing. While we should aim to make sure (1) that our submissions are complete with regard to the assignment requirements, and (2) that we are aiming at more active types of learning and understanding, we’ll want to also make sure (3) that it is clear to our graders that our assignment does both of (1) and (2).

I’ll say more about this on a forthcoming resource page when I talk about the “expert problem.” But it’s enough for us now to understand that grades are not technically about our level of understanding or intended completeness, but the demonstration and evidence of that understanding and completeness.

Putting it together: What is a “B-range paper”?

Based just on our reading of the FAS statement, a “B-range paper” (that is, a paper that would receive a B-range score), is generally a “good” paper.

“Good” in the way we’ve unpacked it means that:

- It is complete, with all main requirements met, and no or very few omissions;

- It demonstrates understanding, based on the course materials (readings, lectures, etc);

- It develops active engagement, providing some critical analysis, synthesis, evaluation, or otherwise going beyond merely repeating the content you are studying and explaining; and

- It gives clear evidence of the above, clearly communicating these items to the grader.

Where exactly in the B-range it might sit will depend on how well each of these is accomplished. But hopefully this helps clarify what a “B-range” might generally mean according to the FAS Statement. At the same time, it might help you see that these standards for a B-range score at UofT can be different than you may be used to in secondary school: the same letters, standing in for different things.

Click here to scroll to top of page.

Assignment grades versus course grades: the FAS Statement in context

You might have noticed that the summary I’ve given above for the FAS Statement on What Grades Mean does not actually work for many assignments. (I’ll give some examples below). It’s important to understand that the FAS Statement is better used to describe course grades rather than assignment grades alone. Why? Well, we might test or measure for these different aspects of grading across several assignments, rather than within every assignment.

Consider an illustrative example:

In first and second year philosophy courses, it can be pretty common to have an exam split into three main sections: (1) multiple choice and true-or-false questions; (2) short answer questions; and (3) a longer essay question. The first section is usually meant to test whether you can recognize a correct answer, such as which author a quote or theory belongs to, or what a key term’s definition is. The second section requires that you can clearly recall and summarize ideas in your own words, such as understanding one author’s argument and a response to it well enough to communicate it. The third section usually requires more synthesis and analysis, such as creating and defending your own argument in response to a prompt, building on that understanding.

Each of these three sections evaluates different types of understanding, and we can see that each of these sections roughly resembles what the FAS Statement says for a C-range, B-range, and A-range grade respectively. It might be that almost every student does very well on the multiple choice section, but only a few students get high scores on the final essay section, since that final section requires not only memorization or recall, but also active synthesis, analysis, and depth of engagement with course contents.

Now imagine that instead of one exam, we split it up into three separate tests. The first test is just multiple choice. The second test is just short answer questions. The final test is just essay questions. This would still seem to test different types of engagement and understanding, just across different tests rather than within one final test. We might expect that a lot of people do well on the first test, and that only a few do well on the last test. In this case, doing well on the first test will not necessarily guarantee a strong course score, since getting an A-range score on that test will not usually require “strong evidence of original thinking.” Neither will doing badly on the final test guarantee a low final score. This is a bit oversimplified, but already we can see that the FAS Statement cannot apply to every assignment in the same way.

In fact, many introduction to philosophy courses are structured or “scaffolded” similar to this example. Quite often, your first essay will be an “exegetical” essay that just summarizes someone’s view in your own words. Then the next essay might require that you just explain an objection to someone’s view and reply to that objection. And then the final essay might require that you do all of these in one paper: summarize a view, take a position of your own on that view, and defend your own position from an objection. This approach to “scaffolding” assignments in a course means that we start by testing the skills and understanding described by the C-range and B-range of the FAS Statement, and build toward the more involved skills reflected in the B-range and A-range parts of the statement — we make sure you can grasp the ideas, before asking you to actively do things with those ideas.

Finally, consider that different courses can sometimes have different standards, since we can scaffold learning across courses and not only within them. For example, a fourth-year seminar will often be far less focused on testing your recall and understanding of a given text (skills you hopefully practiced and developed in prerequisite courses), and much more focused on your own creative analyses; but a large introduction to philosophy course might focus more on your ability to summarize ideas clearly and accurately more than to provide your own analyses.

In general, we can see that the FAS Statement will not apply to every individual assignment or rubric. While my above summary of the statement helps us to understand how the FAS Statement defines what grades mean, we will have to critically reflect on that statement in the context of our specific assignments.

To this end, you might ask yourself (or your instructor) questions like: How does this assignment fit into the course’s main learning objectives and outcomes (“CLOs” for short)? How are this assignment’s goals similar or different to the other course assignments’ goals? Is this assignment focused primarily on explanation, analysis, or both? What does “evidence” of analysis etc look like for this assignment? How does the FAS Statement on What Grades Mean apply to this assignment’s rubric? If there is no rubric, is it enough to rely on the FAS Statement? What are the main areas for evaluation for this specific assignment? What are the verbs or action words I can see in the assignment instructions, and what does that tell me about how the FAS Statement is being used, or in general about what my goals should be?

Now that we’ve given some more context to what grades mean within and between courses, let’s say something about GPAs.

Click here to scroll to top of page.

“What is a good GPA?” Understanding the cGPA

In our school Reddits, I often see students asking “What is a good GPA?” The answers in those threads range widely, suggesting a fair bit of disagreement or uncertainty. Answering this question typically needs some further context than those answers offer: good for what?

While it might sound trivial, different people have different learning goals, and what’s “good” for one person may differ from another. If you’re asking what cGPA is “good” to be competitive for applying to graduate school, that’s going to be quite different than “good” for applying to an internship, for being able to graduate, or for maintaining financial assistance, etc. If your main goal is to improve over time, what’s “good” might look different than for someone who just wants to pass their remaining courses.

We can still say a few general things about cGPAs at UofT.

First, some context: what are GPA and cGPA?

GPA stands for “Grade Point Average.” It is a way of simplifying your course grade on a four-point scale. Different schools will calculate these differently, and the transcript will usually give a guide on how to translate these to help with discrepancies between schools. For our purposes, the same FAS Statement on What Grades Mean defines the GPA value for each letter score (click to open in a new tab).

A cGPA is a “cumulative Grade Point Average.” This gives a weighted average of all your course GPAs, treating full-year courses a bit more heavily than term-long courses. You can use this GPA Calculator from UofT to tinker around with cGPAs (click to open in a new tab). Because a cGPA considers letter rather than percentage scores, and because it averages course GPAs rather than reporting the GPA of average course grades, it is not a particularly fine-grain measurement.

Overall, cGPA is a heuristic, a sort of shorthand that gives us a quick sense of how a student is doing. Still, while heuristics can be very valuable in the right contexts, all heuristics have their limits. I explain a few example “cautions” later on below.

A “good” cGPA according to policy

Since a B-range grade is “good” by definition in that FAS Statement, then an officially “good” cGPA is between a 2.7-3.3. When I see these cGPA-related posts on Reddit, many comments instead suggest 3.5-3.7. While those are also good, and would even be competitive for many graduate programs, our policy more clearly explains that those are “excellent” while a “good” starts much lower. We have a tendency to set the bar for “good” higher than it often is (maybe because we’re used to high school standards still!)

Some cautions about cGPAs

It’s easy to compare ourselves using cGPAs. I want to caution against giving them too much weight. Putting aside equity issues, and the fact that students are not reducible to their grades, consider a few features of the mathematics involved. You can skip this section if maths aren’t your thing, but I think this is worth knowing.

First, the cGPA is calculated as a weighted average of your GPAs, not as the average of your weighted course percentage scores, and this creates some problems. Consider an illustration:

Let’s say it is my first term at UofT and I took five classes, each of which was 0.5 full credit equivalents (FCE). I did exceptionally well, except for one course where I forgot to submit a paper on time. My final scores were 85, 90, 91, 87, and 72. The average of all these percentages is 85, and if we were calculating cGPA just from that average, then I would have a 4.00 cGPA this term. But that’s not how cGPA is calculated. Instead, I first have to convert each of those grades to a GPA. I end up with 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, and 2.7. My cGPA is the weighted average of those GPAs, which is 3.74 not 4.00. That feels like a big difference!

In fact, because I have a single score under a 4.00, I will never be able to have a 4.00 cGPA just by doing well in future courses, unless I get that course removed from my transcript. (The average of a heterogenous set of positive numbers will be less than the highest value in that set). Even more impressively, if I had only that one 2.7 in my whole undergrad of 20.0 FCE, and the rest of my courses were 4.0, my final cumulative cGPA would still only be 3.97. After 130.0 FCE (about 26 years, full time), I can get to a 3.995, and which might get rounded to 4.00… all because of that single 2.7.

Second, since GPAs are assigned upon letter grades, not every percentage point matters equally. If I scored a 73 instead of a 72, that course’s GPA would jump from 2.7 to 3.0, and my cGPA for the whole semester would jump from 3.74 to 3.80. But if I scored a 71 or even a 70, I would still get a 2.7 GPA for that course. In part for this reason, some universities don’t even assign final percentage grades, only the letter grades.

Third, there are many paths to a given cGPA. Consider two scenarios: (1) I am taking courses in two departments. I’m quite good at courses in one department, but not very good in the other. My scores end up being 85 and 88 in one department, but 57, 60, and 63 in the other. (2) I take five courses, all of which are clustered between a C+ and a low B. My final scores are 68, 68, 70, 72, and 73. In both cases (1) and (2) my cGPA turns out to be 2.6. But those two stories seem quite different, and meaningfully different. cGPA alone can’t tell us what a student’s story is overall.

What is this math meant to show? Ultimately, the cGPA is a heuristic—a useful guide—and certainly cannot tell us the fuller story of how a student is doing. In the very least, we can see how a 3.7 cGPA is more than just good. The 3.74 in the above example is excellent, made possible by several 4.0 scores. Meanwhile lower cGPAs are not necessarily bad, and can just reflect a few outliers.

Ultimately, what counts as a “good” grade depends on what your own personal goals are. By policy, however, a “good” cGPA starts lower than many students suggest.

Click here to scroll to top of page.

“Where did I lose marks?”

If you have been reading through this page in full, and reflecting on the language of the FAS Statement on What Grades Mean, then you’ll already likely have a sense of how I answer this common question. While in some cases, a grade might be reduced for reasons outlined in course or assignment policies (perhaps the grade is adjusted because of policies concerning late submissions or going over the wordcount), most often we are not in fact grading students down, but up.

When we grade, we start at zero. Assignments then earn marks according to the assignment requirements and rubrics, by demonstrating their competencies and mastery of course learning outcomes. If I don’t submit an assignment, then I have not given evidence that I met any of the requirements, and have not given any evidence of meeting course outcomes, so the grade will stay at zero. If I submit an assignment that meets only some of the requirements, that incompleteness might warrant me a D-range or C-range score as I start to show a more complete assignment and active understanding. As I continue to meet all the requirements, to meet them well, and to demonstrate evidence of my active understanding and mastery of course outcomes, then my grade will increase as well. We earn marks up from zero, we don’t have them deducted from one hundred.

Here’s a very imperfect but possibly helpful analogy: grading and shotput. Shotput is a type of competitive track and field sport, in which contestants throw (put) a heavy ball (the shot) as far as they can. Their score is measured as the distance the shot is thrown, as long as it falls inside the boundaries. The further you throw it, the higher your score. Throwing a shot far requires building up specific strengths, but also practising very specific movements and form to make the most of those strengths. We can imagine that a seasoned shotputter makes a mistake and releases the shot too early, causing it not to go as far (maybe 20 metres instead of their usual 22 metres). It might seem odd for us to ask where the extra two metres were “lost” exactly; nobody is deducting distance because the throw wasn’t in good form. Rather, the error in their throwing form meant that the shot couldn’t go as far. If I make several errors in writing my paper, then those errors mean I am not giving enough evidence of understanding or of completeness needed to hit higher grade thresholds. Perhaps I didn’t even follow the instructions carefully, and ended up throwing the wrong type of shot in the wrong direction! They might not measure my distance at all if I wasn’t following the guidelines.

Perhaps instead of asking, “where did I lose marks?” I might suggest questions like the following (asked to yourself first where possible, and then to your graders):

- What feedback mattered most for my score?

- What part of the rubric did I score lowest on? What changes would have helped push my assignment into the __ grade range?

- What single change to my submission would have the largest overall impact on this mark?

- I’m having a hard time connecting this feedback to the rubric. I thought I had done __ in the ways the instructions asked for, but the feedback says __ instead. Can you tell me more about why that was not enough to earn my desired grade, or what I could have added to bolster that grade?

- I’m having a hard time understanding how I could have practically improved on __ in the way the feedback / assignment called for. Could you recommend one or two concrete strategies or supports for next time?

Let’s start wrapping up this page by saying a little more about feedback and/versus grades.

Click here to scroll to top of page.

“Why is my feedback so brief?” Understanding grading context, and feedback as a scarce resource

When I was in undergrad, I often received very brief feedback. Testimonies from my students often suggest the same. It can be frustrating to receive brief, vague, and generally unhelpful feedback that might only be a few words long. Being told something is “unclear” or receiving a general “good” or even just an expressive “?” is not particularly helpful guidance. Meanwhile, we might not receive any marginal feedback, and instead just receive a few sentences at the end. These too can be vague, especially since they won’t often point out the specific parts of the paper or assignment the comments are targeting. So, why is feedback often so brief?

There are many common and possible reasons. For example, it’s pretty well established that few students will actually read and engage with their feedback in detail. I do not think that is a good reason to provide limited feedback, to be clear. But I do know many professors and TAs alike who take that as a reason to be brief, expecting students to follow up in office hours for further feedback (see below).

In what follows, I explain what I think are the more common, structural reasons. It is worth being clear that I’m explaining, not endorsing the following. And while I’m going to focus on Teaching Assistants (TAs), since this is most often who will be grading your course work in our departments, similar constraints apply to classes where there are no TAs.

Limited grading contract hours

When a teaching assistant signs onto a course (for many of them, a necessary part of their funding packages), their position has a set number of hours. The number of hours are based on what funding the university has given the department for that course, and generally based on the enrolment numbers. (I say “generally”, because the number of hours I’ve had for 100 students ranges from 70 to 110, a difference of about 50%!). I looked over my last ten TA contracts when drafting this page, and the ratio between the contract size and number of students ranged from 80 hours for 125 students, to 110 hours for 100 students, and averages to about 50min/student for the whole term.

However, those hours are divided across many tasks. When TAs sign onto a course, they are given a form called the “Description of Duties and Allocation of Hours” or DDAH for short. That form outlines how the course hours will be broken down, and there are mandatory items required in that breakdown. For example, courses on the downtown campus require TAs to to attend a certain amount of classes, while there are other hours set for signing and discussing the contract, and often for meeting with instructors to benchmark, holding office hours for students, etc.

For example, in my 70 hour contract, I ended up having only 42 hours to grade all the work by all 100 students, all term long. That’s 25.2min per student. This needed to be broken down further over three papers. That meant I had about 8.5 minutes to grade a student’s 800-1,200 word paper: to not only read it, but also to try my best to understand it even when sentences are unclear etc, to decide on the feedback that would be helpful and to write/edit that feedback, to determine your grade in terms of the course rubric or the instructions the instructor has sent me, to investigate any academic integrity issues, and to upload that grade etc into the online gradebook. In general, the amount of time I have for a short paper has ranged from 8 minutes to 20 minutes, and is often around 12 minutes. It’s less time than it might seem, and it makes it hard to give strong feedback.

Ultimately, many courses are not given adequate hours to do good work (sometimes, the issue is how an instructor allocates those hours, but the upstream problem is that there are too few hours to allocate!). This means a few things, like reading very quickly, and not often having time to sit and interpret unclear writing for what a student might have intended a sentence to do or say instead of just taking it literally or at face value; limited feedback time, and not often being able to give more than a few sentences per paper; and contract breeches, where TAs feel obligated to work beyond their contracted hours in order to do a decent job of grading, thus doing uncompensated labour.

This later point is exacerbated by the use of student evaluations: TAs are expected to use student evaluations to apply for subsequent jobs. If they only worked as much as their contract allowed to (say, that 8.5min per paper), they will often receive unkind evaluations, and this threatens their future job applications and security. So, many of them feel coerced toward working beyond their hours.

Ultimately, not everyone has the luxury of working beyond their contracts, and those who do might only add a few additional minutes. So, it is common in general to provide only brief feedback. This is often outside of a grader’s control, but something that can be mitigated if the grader has office hours in their contract (use them if so!). If the grader does not have office hours, instructors are expected to have regular student contact hours by policy. Reach out to them too!

Course and faculty deadlines

A related source of grading-time scarcity has to do with course and faculty deadlines. In ideal circumstances, TAs are usually given two weeks to grade a batch of assignments. This is not always possible.

Perhaps there are weekly reading responses the TA needs to grade, in which case they want ideally to give some feedback to students before the next weekly assignment is due. This might mean grading a large number of reflections in a very short turnaround. When the TA is taking multiple courses, and perhaps grading in multiple courses, there might be very limited time in a given week to grade, even if we did try to ensure there were more grading hours in the contract itself. While best practices often suggest that instructors assign more regular “lower stakes” assignments, this is often in conflict with how many hours are available in the grading contract, and how much time graders have in which to use those hours productively. This, in turn, can often facilitate briefer feedback.

Or, perhaps they are grading a final exam. Policies often require that instructors submit final course grades just five business days after an exam. This again means very little time to grade, and thus less time to prioritize on feedback. Similarly, perhaps the instructor wants to assign a midterm that covers half the course content. As you likely know, there are policies about when to return grades to students before a drop deadline. The instructor might make the midterm due quite close to that deadline, meaning that TAs have very little time to grade and give feedback. (Both of these are reasons why you will only rarely receive feedback on midterms and exams!)

External sources of (further) feedback

Coupled with the often-limited grading hours, TAs may limit the feedback they provide because that feedback is available through other external sources. I’ll mention just three here.

Course materials: First, as mentioned later in this page, feedback might already be covered by course materials. For example, instructors might take up key problems or answers in class, or post them through the course website. Or, they might have outlined key things to avoid in lecture, in assignment instructions, or in the rubric. In these cases, it may not be the best use of time to repeat feedback that is already available elsewhere.

Previous feedback: Related to the above, graders may skip repeating feedback they gave on previous assignments in favour of giving new and further feedback. If I spent the first assignment commenting on people’s citation styles and giving them links to supports, then I know that feedback is already available to them, and that they are meant to be accountable to that feedback. Repeating those comments could be helpful (if a student was trying to improve but still needed further guidance), but it may seem more helpful not to repeat the same feedback over and over, and instead to identify other areas of improvement. Finally, this can apply not only within a course, but between them. If you are registered in a third year course with prerequisites, it may seem fair to expect that you already had many opportunities to receive feedback on basics like validity, soundness, or key prerequisite concepts. A grader with limited time may assume that you likely received the more basic or common feedback in previous courses, and that you have access to this previous feedback, and thus prioritize more advanced areas for improvement. This is one reason I recommend reflecting on your previous feedback occasionally, and keeping a feedback journal (opens in a new tab).

Office hours: Finally, TAs will often be given student contact hours via office hours. We can use these hours as an extension of the time available for providing (additional) feedback. If I have very limited grading time, I might give students just brief guidance, hoping that they then choose to follow up on that guidance in office hours for further discussion. When a TA leaves brief feedback like “unclear” but doesn’t elaborate on how or why it is unclear, it might be because they are hoping either (a) that students will be able to use that feedback to examine their own writing and investigate why it might be unclear, or (b) if they cannot figure out why it is unclear on their own, that they then will come to office hours to discuss further. When these office hours are available, they can be an external place for providing that additional feedback. Thus, they can be considered a motivation for permitting just brief feedback.

Limited feedback across the grading scale

Another habit I have observed is that feedback clumps around the middle of a grade range. That is, students who score in the high C to mid B range will often receive more feedback than students in the lower and higher ends of the grade spectrum. Sometimes this is a deliberate strategy about how to prioritize grading time, giving feedback to those that seem more likely to benefit from it (an assumption I would contest). Other times, it is a consequence of the contexts of grading, and it’s these I’ll focus most on.

Based on conversations I’ve had with instructors and TAs, there seem to be a few reasons for these feedback discrepancies, which I’ll summarize briefly below. Again, I am not necessarily endorsing the following, just explaining. My hope is that explaining it helps to empower you to seek further feedback, and to understand the possible upstream reasons why that feedback is limited.

At the higher grade end of the grading scale: Students who are used to getting higher scores are often used to receiving limited feedback. I know I received little feedback in my undergrad, and other students report the same to me. Here’s a comment I recently received in a course evaluation: “It did not occur to me until taking a course with C that I have never received any writing support. To elaborate, I am in my fourth year, and I have been writing argumentative essays for years. While my grades have often been in the A range, feedback only focused on content, so I assumed my writing was good. I identified more areas of improvement in my writing practices from C’s workshops than any feedback I have received on papers.” My writing workshops in this specific course were relatively brief, and so even a small bit of writing support somehow was more than this student received in their previous three years. Why might this be? Here’s three possible reasons, and my discussions with TAs often affirm them.

- First, many TAs are students who also did well in their undergraduate, and this in turn means that many of them did not receive substantive feedback! It is difficult to provide feedback you’ve never seen emulated. Moreover, TAs often receive very brief training for their first appointments (sometimes just two hours or so), and that training rarely prioritizes these more nuanced grading practices. So, many TAs are left without the emulation or support to provide constructive advanced feedback, unless they seek out their own further professional development or practice over time.

- Second, TAs are often grading as part of their funding packages, and (often as a result) are often grading outside of their own realm of expertise. They might be reading papers for the first time alongside you. In the courses I’ve taught, my TAs have almost never read even half of what I’ve assigned, if they’ve even seen the debates before. Importantly, TAs in most courses will rarely have a lot of time to read those papers closely without breaching their contracted hours. They also might not have been paid to attend every relevant lecture. Overall, TAs might not have been given adequate resources to engage assigned content at the level of depth that would help them provide more nuanced feedback. To be clear, this does not entail that they are unqualified to grade your work. Rather, it means that they do not always have the resources to be able to provide nuanced feedback about content.

- Third, providing constructive and nuanced feedback often takes time. But we’ve identified that this time is not always available. If I want to provide feedback about the technical reasons why an argument doesn’t work, or about how to take already clear writing and make it even more concise, this will often take more time than I have available to me.

At the lower grade end of the grading scale: Students who are scoring in the C-range or below may receive more limited feedback for a few reasons, several of which are similar to the above.

- First, because TAships usually self-select for students who got higher scores in undergrad, those TAs will have less familiarity with the feedback useful for lower-scoring assignments. A common assumption I’ve heard from instructors or TAs is that (a) giving more feedback would be overwhelming to students who receive lower scores, or (b) would otherwise impact their self-esteem when coupled with the low score. I’m not convinced that these reasons are unique only to students who score lower on any given assignment, and thus that they are good motivation to give unequal amounts of feedback to them specifically, but they seem to be common sentiments. So, brief feedback is sometimes just intended as precautionary or protection to avoid overwhelming or demoralizing students.

- Second, it might be that the assignment scored in that range just because of one significant error that may be complex but important to resolve. In this case, it might appear useful to focus on that one significant error and ways to improve it, leaving other feedback aside. This may again be especially useful in cases where there is very limited grading time: prioritizing the one item that seems most useful for improvement.

- Third, some instructors and TAs genuinely believe that students with lower-scoring assignments are less capable of responding to feedback, or necessarily care less about their coursework, and that feedback is thus less useful to them. That is, some instructors suggest that because a student does not complete a given assignment well, that this is predictive of their ability to use feedback. Alternatively, they might believe that these students don’t care enough to even look at their feedback, regardless of their potential ability to build on it. Spending less time on feedback for these students, it’s argued, might further allow more feedback time for other students who would make better use of it. This strikes me as an obviously spurious overgeneralization. While it’s certainly true that some students will score lower because they do not care about a given course or assignment, might be taking it credit-no-credit, or struggle to use that feedback meaningfully, this surely does not generalize across all students in a given grade range, and I am not convinced it is not a strong reason alone to portion feedback according to a grade.

Finally, a note on charity. While the above observations are based on conversations I’ve had with some TAs and instructors, it would be wrong to assume that most or all people grading your work have this mindset. Moreover, all these above points are about the generalized patterns of how feedback portioned across the grade range, across courses and assignments. There may be good reasons on a given individual assignment to provide less feedback, and I’ve hinted at some above. My cautions and objections above are not meant to target these cases. Rather, what I’m commenting on here is those graders who on the basis of a general grade or performance level choose to give less feedback, rather than on the basis of a specific student’s or assignment’s needs. As a student, you may not be able to tell these choices apart; I am just providing this information to help explain some of the many structuring reasons why feedback can be limited (note how limited training, exposure, and grading time structure much of the above). The only way to determine whether these reasons apply to your specific feedback will be to discuss with your graders themselves.

So what? Putting context into practice:

In short, the above sections outline that (1) limited available grading time and training, (2) administrative deadlines and course design best practices, and (3) assumptions about what is most helpful to students, can all lead to brief feedback. While this might reflect choices your graders made, more often they come down to inadequate resources.

However, we’ve also identified that limited feedback can be offset by alternative sources of feedback. Here are some final recommendations to end on.

- Spending time on feedback reflections / developing a feedback journal: On another page, I offer guidance about how to read and engage with the feedback you receive (click to open in a new tab). Students in other courses have reported that working through these reflections and guidance help them make sense of even limited feedback, and I offer some specific examples of engaging brief feedback. A more committed version of this practice is to build a feedback journal, which is also described on the previous link. Just a few quick tips from that page:

- Investigate in context: Take the brief feedback as a clue about where you could have revised further. Spend some time investigating the given sentences or arguments, asking yourself why someone else might not have understood what you meant. Where might your intentions not have appeared on the page?

- Compare with peers or other readers: Did any other classmates receive similar feedback that you can use for contrast or context? Could someone else who isn’t as familiar with your assignment help identify what specifically might have seemed “unclear” in a given sentence (or for similar brief feedback)?

- Review previous feedback: Is there anywhere else that you received similar comments, but in more detail? Could previous feedback shed some light on the current feedback? This might be from a different assignment, or earlier or later within the same comment.

- Reviewing existing course materials and lecture notes. As mentioned above, sometimes limited feedback is caused by or offset by existing available feedback. Did you receive a comprehensive assignment package or rubric, which might clarify the feedback you received? (Hint: is the grader using similar verbs or language that the instructions or rubric does?). Did the instructor cover the assignment in detail during lecture, or announce that they will be taking up answers further in class? Check over your notes again, ask your peers, and otherwise make use of office hours or discussion boards to inquire further.

- Make use of office hours. Instructors are expected by policy to have regular contact hours with students. TAs typically have some office hours in their contract too (though not always). These are excellent places to talk through the feedback you receive and to request further feedback where possible. In many classes, I find my office hours drastically underutilized, and there have been other courses where I assigned TAs many contact hours that barely get used. These are valuable opportunities that few students take advantage of. Office hours are open to all students, and are not just meant for disagreements, drafts, etc. Importantly, when TAs do have office hours, this necessarily means they will have less time to grade. If my original contract is 50 hours, the more of this is spent on meetings, the less can be spent on feedback. While office hours are generally already meant to be spaces where you can engage and get support, you might take this trade-off as further motivation to make use of them!

Click here to scroll to top of page.

The relationships between grades and feedback

I say “relationships” with a plural because there can be many types of relationships between feedback and grades. You probably already know this: you might be used to some feedback that explains the grade you got; but you might also have times when your feedback seems utterly irrelevant to the main rubric; and in some cases you may barely get more than a sentence of feedback. It can be hard to determine how the feedback fits with or explains your grade, and in general:

There is no necessary relationship between your grades and feedback.

Consider straightforwardly: I could write feedback on how to improve an assignment without actually assigning it a grade, and without having even seen a rubric. If there are misrepresentations of texts, underdeveloped arguments, errors with spelling or citation, etc, these will usually be apparent on their own. That feedback might identify ways of improving that are not actually part of the current rubric. And so, that feedback might not be connected to the grade, even if it is likely useful for improvement.

Indeed, there can be good reasons for choosing to comment on items not graded by a rubric. For example, some instructors will “scaffold” their assignments, meaning that each assignment practices a different skill, or builds on the previous assignments. In some cases, the first assignment might be a summary of a paper, while the second assignment asks only for an objection in response to a different paper. In this kind of setting, it might not be too helpful to spend all my grading time on explaining all the errors in a summary, since those arguments will not appear in future assignments, or since those errors might otherwise not be transferable to the following assignments. If I had an abundance of grading time, I might point these out. But, as we discussed in the previous section on this page, graders rarely have abundant time. So instead, I might focus on clarity, structure, citing, structure, etc, since these are more transferable to the next assignments, and then discuss the remaining summary-specific content if the student comes to office hours.

Similarly, if the first assignment didn’t penalize for incorrectly formatted citations, but the second assignment would, then I might give guidance on your citations even if it did not impact your current grade, precisely because it will in the future. This could also be true between courses: in an introductory course, I might comment on things that will be relevant to grades in upper year courses, even if there is lenience in the current course. Conversely, in upper year courses, they may assume you received that basic writing guidance in your prerequisite courses, and so are less likely to (e.g.) comment on validity, soundness, grammar, or citation errors, even if these may have impacted your grade directly.

Meanwhile, and as mentioned in the previous section, some instructors will take up answers or feedback collectively in class, and guide their TAs to avoid repeating that feedback (since the feedback is already going to be available elsewhere). Similarly, if there is a very detailed rubric or instructions package, then the more “obvious” influences on grades might be left without comments, since they are already covered in those available materials. In these cases, offsetting feedback with class discussions or rubrics can leave the grader more time to focus on feedback that is not already being covered and made available to you, and thus to cover feedback that may not so directly influence your grade.

Finally, the instructor might explicitly ask the graders to focus on specific types of feedback. This often happens for the reasons described above, such as avoiding repeating feedback covered elsewhere, or to better prepare students for future assignments.

So what? Reading grades and feedback

Hopefully the context on this page helps to read feedback more charitably: as a scarce resource, and which is not always just about grading. A few final takeaways:

Feedback can be a guide between the grade and the rubric (and/or FAS Statement). Look in particular for shared language between the feedback and rubric. Are there particular verbs, nouns, modifiers, or other words that appear both in your feedback and your rubric? If so, this can be a helpful guide. Even if there is no assignment-specific rubric, the FAS Statement described earlier on this page can give us guidance. If I see language like “excellent analysis” then this likely correlates with an A-range grade for that grading item; while a phrase like “good grasp” might signal a B-range grade.

Still, we should aim to read feedback for feedback’s own sake, and not merely as a guide to a grade. Feedback is often meant to identify strengths and areas for improvement, and to thus guide your development throughout a course, discipline, or degree. It can separate out from your grade, and there are other resources to help interpret the grade (mentioned above: office hours, instructions, rubrics, course lectures).

Of course, if your feedback seems utterly detached from your grade, and if there is no rubric to guide your interpretation of the grade you received, absolutely reach out to your grader in office hours or their preferred form of contact for clarification!

I’ll offer more tips on how to engage with feedback on another page (click to open in a new tab). Have other questions about grades and grading? Email me to chat or book a mentoring appointment!